Chapter 10 – The First Lotus Super Seven

- International 7 Network

- Feb 25, 2021

- 5 min read

by John Watson

The Dilemma for Lotus

It is said that every Seven that was produced by Lotus up to the end of Series One production was sold at a loss. The choice for Lotus was a simple one: either cease production of the car altogether or radically re-design it, making drastic cost savings. Influencing their decision was that Club Racing in the UK was getting ever more popular as one of the entry levels into motor sport and since the advent of the “A” Series powered “America” cars, the U.S. market was really opening up. As we know today it was decided to re-design the car!

CHASSIS AND BODY:

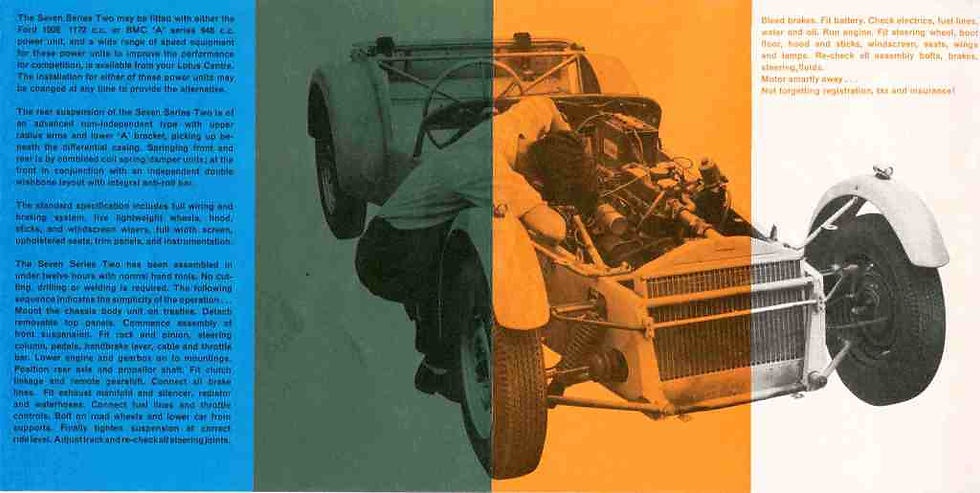

Considerable cost savings were made by simplifying the chassis and reducing the number of members, particularly those towards the rear of the car. In addition, the expensive double curvature aluminium body panels that required specialist craftsmen, skilled in the use of the English Wheel, were re-designed and replaced by items made with glass reinforced plastic. These included rear and front cycle wings (‘clamshell’ wings that were fitted to the U.S. “America” model had always been made with g.r.p.) and the nosecone which was of a very similar style to that on the front of Lotuses Type 18 Formula Junior race car. Further savings were made by not having the aluminium floor extending under the rear axle and around the engine bay. A major improvement was that there was now aluminum sheeting behind the seat backs preventing water coming through to the seats from the rear wheels.

SOURCING OF PARTS:

Not many motor manufacturers were happy to sell their car parts in bulk to the likes of Lotus as they feared getting a bad name for unreliability. John Standen who was Chief Buyer found that despite this there were good deals to be had with Standard Triumph. For some years the Seven and other Lotus models had incorporated front uprights, and trunnions from both the Standard 8/10 and Triumph Herald as well as steering racks from the latter.

REAR AXLE:

The BMC axle from the Nash Metropolitan had been installed in both the Eleven ‘Sport’ and ‘Club’ models since 1956 and on the Seven since production began. This item was used because of its larger brake drums and the wide choice of final drive ratios it offered. Standen was able to source an alternative axle from Standard Triumph’s Standard 10 which was both cheaper and lighter than the BMC item which still offered a choice of ratios (4.1:1 and 4.55:1). It had smaller 7” diameter brake drums which were matched by using drum brakes from the Triumph Herald at the front. This enabled the wheel stud spacing to be naturally common to all corners, a feature that the Series One had always lacked.

REAR AXLE LOCATION:

To make further savings it was important to reduce the number of engineering operations required on the axle to install it into the Seven. Previously with the Series One BMC axle location was by upper and lower trailing arms and a brace to prevent lateral movement. With the Standard 10 axle location points for the upper trailing arms were already there and it was decided to use an ‘A’ frame for lower location utilising the differential drain plug thus doing away with adding any further fixing points to the casing. So there were two upper trailing arm points and one lower ‘A’ frame location point in the centre doing the job of both lower location and lateral bracing. Later the drain plug fixing was to be replaced with a bracket welded to the bottom of the differential housing.

STEERING:

The first Sevens, like the Elevens before them, had used a left hand drive Morris Minor steering rack placed upside down. The rack was placed behind the centre of the wheels and the column had two universal joints and was routed along the floor alongside the engine block. Towards the end of Series One production lhd Triumph Herald racks were used in the same way. With the Series Two more savings were made as the steering column now took a straight route from the dashboard to the rack now more conventionally located as a rhd item to the front of the centre of the front wheels.

WHEELS:

The Series One had used 15” x 4J disc wheels, firstly similar to those used on the Turner Sports car and later as used on Triumph’s TR3 sports car or 15” x 4J MGA 48 spoke wire wheels as an option. Again, for the Series Two Seven, Standen was able to source a good deal with Standard Triumph for the 13” x 3½J items used on the Triumph Herald. In 1960 13” wheels had become the fashion and had the added advantage of lowering the centre of gravity of the car, a must for competition events. The wire wheel option was no longer available.

ENGINES AND GEARBOXES:

Production of the Series Two Seven commenced initially with the two basic engine/gearbox options from the Series One. The original Ford 100E 1172cc sidevalve unit with associated 3-speed gearbox and the BMC “A” Series 948cc overhead valve unit and associated 4-speed aluminium cased gearbox either in Austin A35 form with a single SU for the home market or as fitted to the Austin Healey Sprite with twin SU carburettors in the “America” model for the U.S. market. The Coventry Climax engine option was no longer available.

In January 1961 Lotus started to install the Ford 105E 997cc overhead valve unit with associated 4-speed gearbox from their Anglia car. This engine had been fitted in Series One Sevens by some dealers for the past year. Being of over-square cylinder design, it was much more freely revving and more tunable than the longer stroke BMC “A” unit. In fact it was the chosen power unit for the Lotuses Formula Junior open wheel race cars, the Type 18, Type 20 and Type 22 which were so successful with the help of Cosworth Engineering.

In the early 1960s Ford did not have a remote change for their 4-speed gearbox. To get the gear lever back adjacent to the steering wheel a remote from the Triumph Herald was used with a wedge shaped adaptor plate along with some machining of the connecting interfaces. The end product was surprisingly effective.

THE FIRST SERIES TWO PRODUCED:

Strangely enough the first Series Two is nothing like I have described above. Instead it featured a pointed boat tail and raised instrument scuttle crafted in aluminium. Research seems to suggest that the car had these features very early on in it’s life, certainly as far back as the early 1960s. Was the work commissioned by the first owner because he disliked the new Series Two g.r.p. body features or was it a factory prototype? The use of cycle wings would suggest the former but who knows?

Photographs by courtesy of: Ferret Fotographics TEL: 01453-543243

Sources and further reading:

Lotus Seven by Jeremy Coulter (198?)

Lotus – All the Cars by Anthony Pritchard (1990)

The Lotus Book by William Taylor (1998)

留言